While the shock at Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has abated since its troops crossed the borders last February, the entire world remains gripped by the battles still raging at the frontline. The incessant bombing of civilians perpetuated in places like Bakhmut – which has become symbolic of Ukraine’s dogged resistance and widespread international support – is familiar to all.

But beyond the frontlines, another, less bloody war is being fought, a war against corruption which Ukraine must also win. In this fiscal and political conflict, the enemy is internal, but nevertheless, a foe which must also be defeated if this nation which has endured so much, is to secure international funds to rebuild the country after the war is over.

For many years, corruption has long been Ukraine’s overriding and most deep-seated issue. Now it is diplomatically sensitive, with critics wary of portraying Ukraine as endemically fraudulent. Before the war, Ukraine was making gradual progress, rising slowly up Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index from 142nd in the world in 2014 to 122nd in 2021.

Dissenting voices believe that Ukraine’s anti-corruption investigations have yet to target the genuinely corrupt. Instead of injecting real reform, they say, the clampdown on corruption has been used by those with a vested interest to frame high-profile financiers who advocate reform of the state system, so that it can be safe for international investment. They allege that the authorities were instead focused on businesspeople who joined the government to help revive Ukraine’s economy after the 2014 revolution. Many of those same officials are said to have fled to Moscow when the tanks rolled in, and they continue to target the investors who sought to bring progress in their own country from afar.

The US, Europe, and the United Kingdom will one day hopefully be able to invest billions in the reconstruction of Ukraine, but for this vital investment to be forthcoming, these and other nations must have complete confidence in both the rule of law in Ukraine, through impartial courts, and uncorrupted offices of state. Sadly, for Ukraine, these pillars of a functioning democratic state have long been beset with public and private corruption. The recent arrest of the Head of Ukraine’s Supreme Court in an anti-corruption probe highlighted once again how deep-rooted the problem remains.

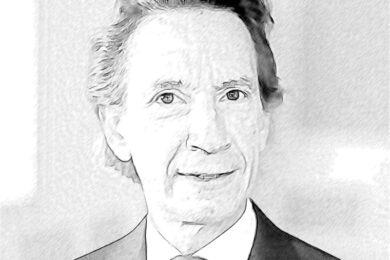

One recent example said to highlight these problems is the case of Tamaz Somkhishvili, a British citizen of Georgian origin. Formerly an executive and founder of oil and gas companies in Russia, after leaving Russia Somkhishvili entered into a public-private partnership in Ukraine in 2007 after his Ukrainian project company, Kyiv-Terminal LLC, won a tender under the Kyiv City State Administration to reconstruct Kharkiv Square.

The development included hotels, offices, shops, restaurants, and transport infrastructure. However, despite the company investing tens of millions of dollars in the project the council eventually decided to terminate the land lease agreement and the whole project in 2013 and withdrew the land parcels previously transferred to Kyiv-Terminal.

This decision led to the termination of the investment agreement, which meant compensation was due for Kyiv-Terminal’s costs and losses. However, the Kyiv City State Administration then failed to meet its contractual obligations and refused to pay compensation for the losses incurred by its decision to terminate the project. This was despite the fact that an independent international appraiser appraised and confirmed the amount of the losses.

Somkhishvili claims that Kyiv-Terminal negotiated with the local City authorities and with the Government of Ukraine for two years to settle the dispute, during which all the government agencies involved agreed that compensation was due. It was decided, however, that the final figure be determined by the Ukrainian courts.

In 2019, the Municipal Court of Kyiv handed down a decision that partially satisfied the company’s claim, awarding damages of $24.5m. But the funds were never paid to Kyiv-Terminal.

The public prosecutor, allegedly acting in the interests of the state, took the position that an investment project with a local authority is the investor’s risk. Perhaps surprisingly, the Court of Appeals agreed. It was, Somkhishvili insists, a decision which tramples on all business principles and international trade laws. Worse still, he claims, it violated the legal rights of foreign investors in Ukraine to fair compensation for losses protected by the UK-Ukraine Bilateral Investment Treaty.

As the result of Mr Somkhishvili’s cassation appeal, that decision was itself dismissed by the Supreme Court of Ukraine, and the case was sent back to the Court of Appeals for reconsideration.

What followed was, according to Somkhishvili’s account, even worse than the court’s apparent efforts to protect the local authorities at the expense of foreign investors. Due to his tenacity in fighting his case and his refusal to accept the alleged injustice meted out by the authorities, and even despite his proposal made in view of the war to end the dispute with a settlement agreement, he has subsequently found himself the subject of what he says is a vicious smear and defamation campaign. The attack, which began at a local level in Kyiv, has grown to become a cross-border effort, seemingly sponsored by the corrupt city of Kyiv ex-officials who fled to Moscow, as well as current officials and politicians in Ukraine, including some members of the Parliament.

Somkhishvili – who refutes all the allegations raised against him – believes that these many officials have corruptly stolen his investment funds for their own commercial ends. He says the reputation attack appears designed to influence the Ukrainian courts in relation to his case and reveals the lengths to which his opponents will go to enrich themselves at the State’s expense. Those behind the apparent defamation campaign, he claims, have also exerted pressure on media organisations which cast doubt on the veracity of the allegations.

This case feeds into a fiercely contested debate in Ukraine over whether the clampdown on corruption is being used to frame high-profile business advocates of state reform. Other prominent investors have raised similar allegations about the process, which in turn seeds doubt within the broader international community about Ukraine’s internal political trajectory. Unsurprisingly given the high stakes, questions are being asked about the country’s ability to absorb billions in European and US reconstruction funds once the war ends. Businessmen like Somkhishvili have raised their concerns at the highest level, including to the US Department of State and the UK Foreign Office. Ukrainian anti-corruption campaigners also share many of their worries.

Before the war, on September 17th 2021, Somkhishvili wrote a letter to President Zelensky, bringing this situation to his attention and appealing for his assistance ahead of the Supreme Court review of his case. In the letter, he highlighted the potential damage to Ukraine’s standing among the investment community because of the way in which his company had been treated. He noted that if President Zelensky, as Guarantor of the Constitution and the rule of law, could not ensure that foreign investors would be able to defend their rights in fair courts, Ukraine would never be able to realise its full investment potential.

The President stated in reply that Somkhishvili’s predicament was a consequence of the unreformed courts of Ukraine, explaining that the court system would change for the better in future. However, the onset of war subsequently hindered any efforts to reform the court system, and the situation failed to improve in the months that followed.

On April 14th 2023, Mr Somkhishvili again wrote to the President in an open letter, setting out the details of the alleged slander and defamation campaign of his opponents and again noting that his treatment did not augur well for future foreign investment into the country. At first, the letter was published by the leading Ukrainian information agency, but following pressure from corrupt politicians, according to Mr Somkhishvili, it has since been taken down from publication.

His case is one of a number which has brought the motivations of those spearheading the powerful anti-corruption investigation into the foreground. It embodies the many reasons why Ukraine could find itself significantly impaired when seeking to raise funds from investors in Britain, Europe, the United States, and other major centres of investment until it purges corruption from its business sector and court system. These ongoing disputes shine a light on why it is so critical that a victorious and peaceful Ukraine after the war is seen as a stable environment in which to invest, free from corruption and a safe place for businesses to transact.

Undoubtedly, while attention is rightly trained on the military operations and the anticipated imminent Ukrainian counterattack, this grinding bureaucratic war is one which will influence whether entrepreneurial individuals will want to risk working for the Ukrainian state again when peace is eventually achieved. It is a fight which all acknowledge is less urgent than the one continuing daily in eastern and southern Ukraine, but one that Somkhishvili believes needs to start now.